Edward Lewis — The Racing Shoe Specialist ③

◁ To Previous Episode ② Click here

Edward Lewis — The Racing Shoe Specialist

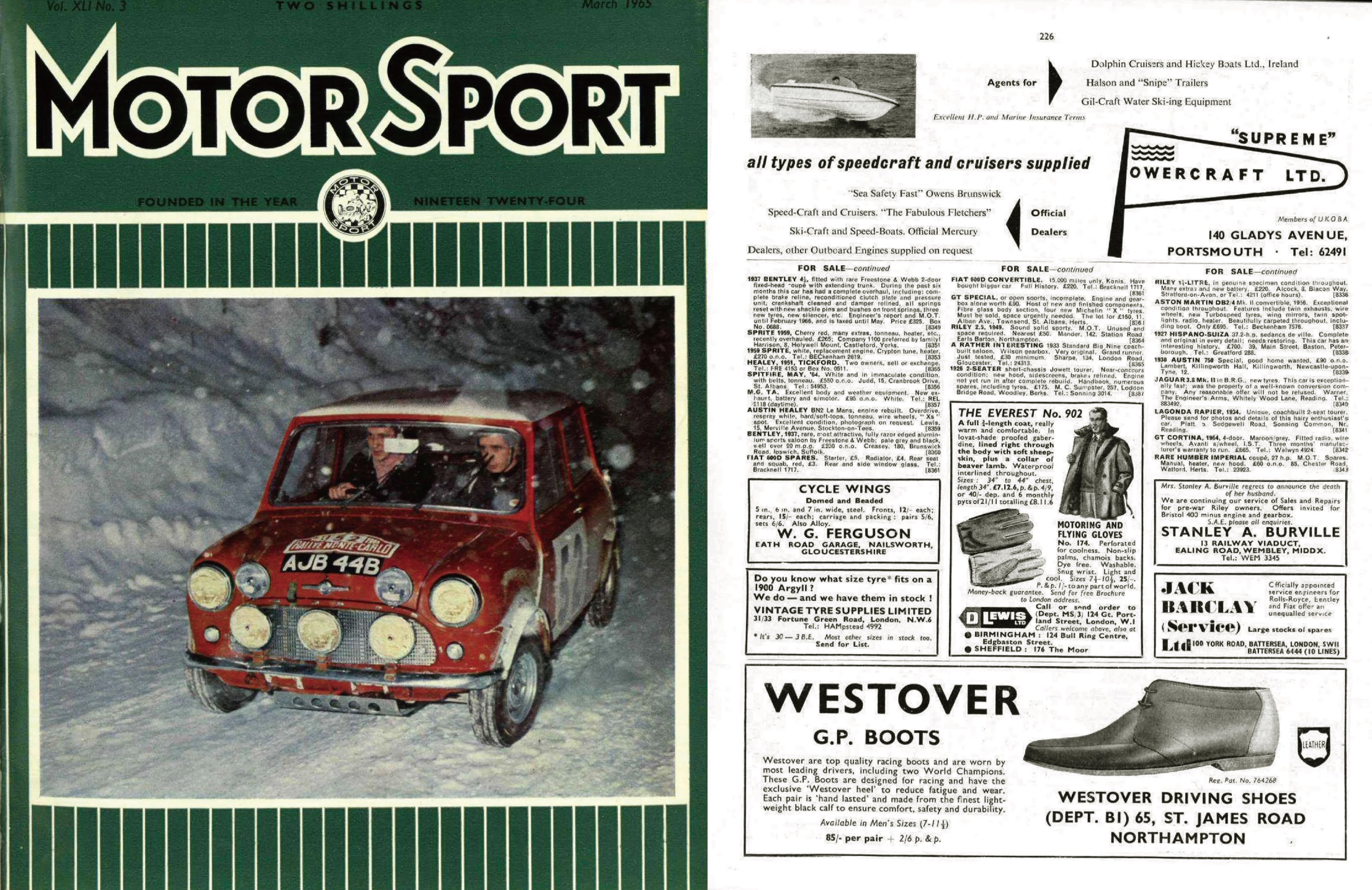

By the latter half of the 1960s, Westover had firmly established itself at the feet of motor racing’s elite. The company was owned and run by Edward Lewis, a self-proclaimed “Racing Shoe Specialist.” In a 1965 advertisement, he described himself quite boldly with that title — a statement that spoke not only of confidence in his products, but of a brand identity built on expertise and pride.

One can only imagine the man behind the name. Who was Edward Lewis?

The records are sparse — fragments of advertisements, scattered mentions in race programmes — yet together they hint at a figure who understood both the mechanics of speed and the poise of style. A craftsman who, in his own quiet way, shaped the footwear of Formula One’s golden age.

The Man Behind the Shoes

Beyond a handful of advertisements and a few grainy photographs, little documentation survives about Edward Lewis the shoe designer.

As for Edward Lewis the racing driver, however, the trail — though faint — reveals something rather intriguing.

Lewis was born in 1922 in Northampton, the son of a family involved in the local shoe trade. While running his own company, Westover Driving Shoes, he also took part in a variety of motor races across different categories — competing not merely as an observer of the sport, but as one of its participants.

It is a detail that lends his work a certain authenticity: the man who designed the shoes was also a man who understood what it meant to drive.

Edward Lewis racing a Riley 1.5 (left, 870 FPA)

Edward Lewis racing a Riley 1.5 (left, 870 FPA)

Snetterton 14 April 1962 ©︎George Phillips Photograph Collection | Revs Institute

The Racer

According to the records of the British Racing Drivers’ Club, Edward Lewis began his racing career in the 1950s behind the wheel of a Riley.

Riley, an English marque that rose to prominence in the early 1900s through its engine innovations, was known for producing relatively affordable yet spirited sports saloons.

During the early 1960s, Lewis is believed to have competed in the British Saloon Car Championship — the series now known as the BTCC — driving models such as the Riley 1.5, Austin A40, and Austin Mini Seven.

He often worked alongside the noted tuner Don Moore, the same engineer responsible for preparing the engines of the famous Lister-Jaguars.

These were not the pursuits of a distant enthusiast, but of a man deeply embedded in the culture of speed — a craftsman who understood both the feel of leather underfoot and the vibration of an engine through the chassis.

In those days, the championship format was a chaotic yet charming affair: cars from different engine classes all ran together on the same grid, with points awarded by category to decide a single overall champion. It must have been quite a spectacle — a patchwork of noise, colour and competition.

Among Lewis’s fellow competitors were some remarkable names. Formula One drivers such as Graham Hill, Dan Gurney, and Roy Salvadori all took part in the same races, piloting Jaguar Mk2s in their respective classes. Even Bruce McLaren, who would later found the team that bears his name, was on the entry list — proof that the line between club racing and Grand Prix pedigree was astonishingly thin in that era.

Equally fascinating is the presence of Les Leston, another racer-turned-entrepreneur who, like Lewis, sold racing equipment, shoes and accessories in London. Leston entered the series in a Volvo 122S — a small but telling reminder that this was a time when competition, craftsmanship, and commerce all shared the same paddock.

Legacy and Connection

For his achievements across numerous races, Edward Lewis was granted lifetime membership of the British Racing Drivers’ Club — a distinction reserved for only the most devoted of competitors.

Remarkably, his connections reached far beyond the circuits. Lewis is said to have shared a close association with Colin Chapman, the visionary founder of Lotus Engineering — the very man featured on the cover of this journal.

Their paths intertwined during one of the most formative chapters in British motoring history: the creation of the Lotus Seven, a car that remains an enduring icon of lightweight engineering.

That story — the tale of Colin Chapman and the Edward Lewis Special — continues in the next Negroni Journal.

©︎Motor Sports Magazine | December 1970

In Search of the Racing Shoe’s Shadow

For years, the pages of Motor Sport magazine were brightened by the regular appearance of Westover Driving Shoes advertisements — and then, quite suddenly, they vanished. The last to appear was in the Christmas issue of 1969. After that, nothing.

As the 1970s unfolded, even the familiar ads for helmets, gloves and other racing equipment began to fade, replaced instead by glossy spreads for cars and components. Perhaps it was simply the natural progression of a maturing motoring culture — or perhaps it reflected a change in Edward Lewis’s own direction.

After 1968, when Team Lotus introduced the concept of full sponsorship livery to Formula One, the sport’s visual identity transformed. Drivers’ attire and car bodies alike were painted in the colours of their sponsors, and the rugged, handmade aesthetic of the early racing era — the spirit embodied by the G.P. Boots — began to disappear.

It may also have been the influence of Jackie Stewart, whose lifelong campaign for improved safety in motorsport reshaped not only the regulations but the very idea of what a racing driver should wear. In any case, the world that once celebrated the craftsman’s touch and the patina of use was changing — and with it, the traces of Westover slowly faded into history.

Graham Hill With Neil Ewart with a Foreword by H.R.H. The Prince of Wales 1977

Graham Hill With Neil Ewart with a Foreword by H.R.H. The Prince of Wales 1977

Published by BOOK CLUB ASSOCIATES

The Last Traces of Westover

Though Westover and its G.P. Boots vanished from the advertising pages of Motor Sport and slipped from public view, the name did not disappear entirely.

By the 1970s, the company had turned its attention to producing high-top racing sneakers — footwear that would again find favour among many professional drivers of the era.

In GRAHAM, a biography of Graham Hill by Neil Ewart, there survives a remarkable photograph: a young Prince Charles, dressed in racing overalls beside Hill himself, both men wearing matching Westover racing shoes. The book even opens with a foreword written by the Prince — a testament to how deeply motoring culture had once intertwined with the British royal family.

For those of us who look upon that image from afar, it represents something quietly enviable: a vision of a nation where craftsmanship, competition, and royal grace could coexist — all captured in the curve of a racing shoe.

©︎Wikimedia commons | Northampton Museum and Art Gallery

©︎Wikimedia commons | Northampton Museum and Art Gallery

The Final Footnote

At the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery — the institution that preserves the long history of the town’s shoemaking craft — there rests a remarkable pair of racing shoes once worn, it is said, by Emerson Fittipaldi during the 1979–1980 seasons.

The design is striking in its simplicity: blue fabric combined with navy smooth-leather guards, a high-top silhouette that feels like a return to the very origins of the racing shoe. On the outer ankle, faint but still legible, is the inscription Edward Lewis Westover — a ghost of a mark that carries the quiet dignity of its era.

It is believed that Edward Lewis passed away in 2015, and I was never able to hear his story in his own words. Yet his contribution to the culture of racing — and to the meeting of craft and speed — remains immeasurable.

His work continues to command my deepest respect, and I intend to keep following the traces he left behind, wherever they may lead, for as long as it takes.