The Racing Shoe Specialist (1)

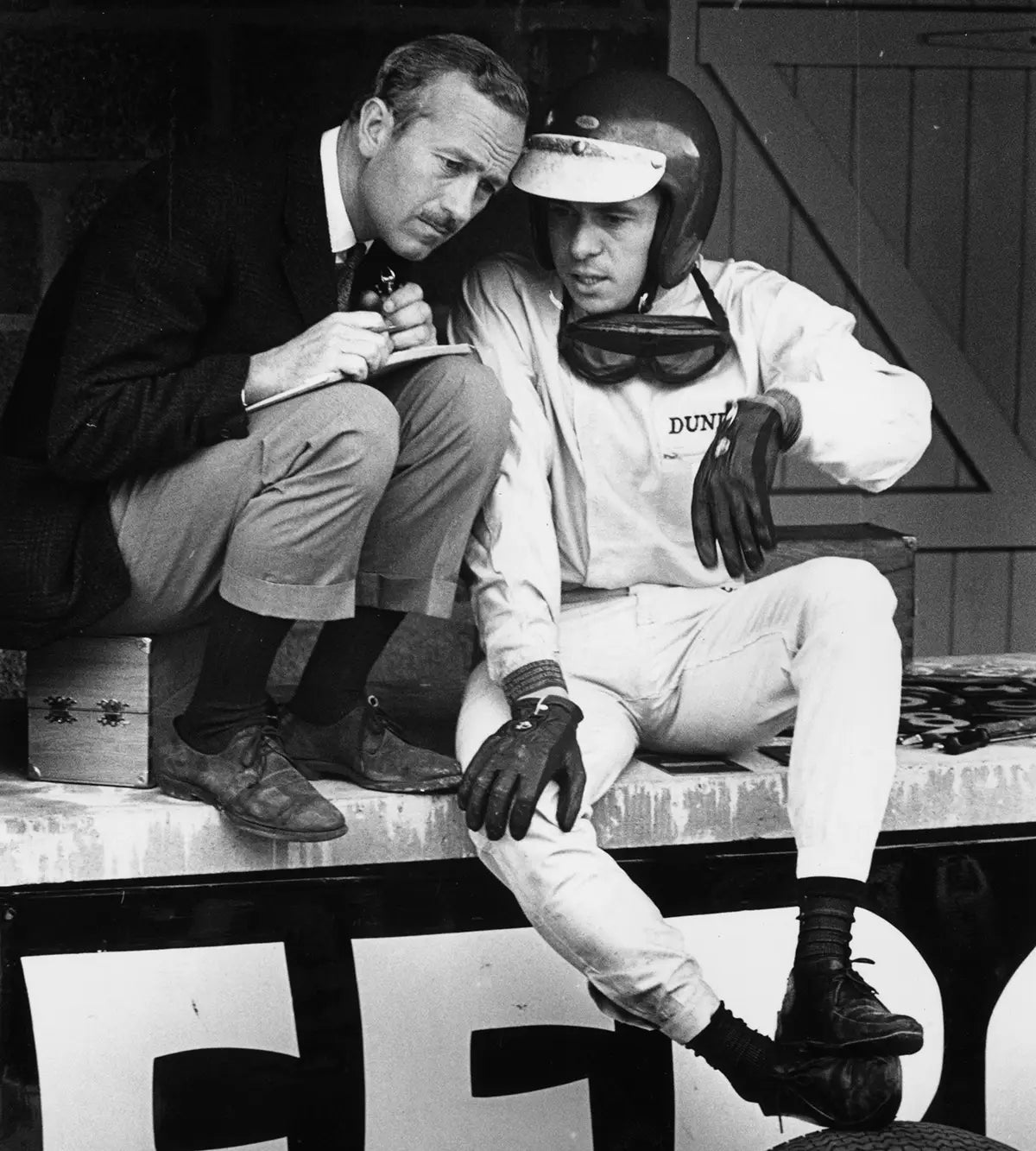

This photograph was taken in June 1964, at Brands Hatch Circuit in England.

On the right stands Jim Clark, then a Formula One driver; on the left, Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus Engineering. The two men lean in close, heads nearly touching, their expressions intent and thoughtful — a quiet exchange between two minds that defined an era of racing.

For those familiar with the golden age of Lotus F1, this image is particularly intriguing. One cannot help but wonder what was being discussed in that moment. Yet for now, let us resist the temptation to speculate — and instead, look down at Jim’s feet.

Just above the ankle, a clean top line and four eyelets. The vamp, neatly split and stitched, appears supple, almost moccasin-like. There is no welt to be seen, and the sole — a wafer-thin piece of leather — gives the shoe an air of both lightness and intent.

The design now affectionately known as the chukka boot — or desert boot, as it came to be called — was once a familiar sight in the paddocks of international racing, including the Formula One Grand Prix. Long before it found its way onto the high street, it served a rather more purposeful role: that of a driver’s shoe. From what I can gather, this photograph of Jim Clark may well be among the earliest instances of its use — a fleeting moment when elegance and engineering briefly shared the same line on the circuit.

The Origins of the Design

Hutton of Northampton "The Play-Boy" | Images sourced from the VegTan blog.

The origins of this low-cut boot are, as is often the case, open to several interpretations. The term chukka — or chukker, as it is also written — comes from polo, where it denotes one of the timed periods of play. Because of that connection, many have assumed that the design itself was born on the polo field. Yet, looking back through the record, that seems unlikely. These were not boots designed for the saddle, but rather for what came after — something a player might slip into once dismounted, in place of his heavy jodhpur boots. A kind of recovery shoe, one might say, meant for ease and comfort rather than competition.

The word chukker is thought to derive from the Hindi for “circle” or “to walk slowly”, which adds a certain quiet poetry to its name. As the story goes, British officers stationed in India during the colonial period adopted the style and brought it back to England — not as sporting kit, but as a piece of everyday elegance that bridged the worlds of leisure and refinement.

Prince Edward, aged 28, playing polo in India, 1922. © PA Images | Alamy

Prince Edward, aged 28, playing polo in India, 1922. © PA Images | Alamy

A Royal Connection

Among the many tales surrounding its origin, one stands out for its romance. It is said that the Duke of Windsor — formerly King Edward VIII — first encountered this style of boot while playing polo in India around 1922. So taken was he with its easy elegance that he brought a pair back to Britain, and thus, the story goes, the chukka boot found its way into English fashion.

The notion that the Duke — a prince of the realm and one of the great arbiters of style in the 20th century — favoured such a shoe carries an undeniable charm. Yet, in truth, there are no surviving photographs or records to confirm it. It remains, as with many fine myths of style, a story best appreciated for its possibility rather than its proof.

By the 1930s, however, the design had certainly taken root. Illustrations and advertising posters from the period show that chukka-style boots were already in circulation across Britain. In 1936, the Northampton-based Hutton Shoe Company Ltd introduced a version called The Play-Boy — a name that perfectly captured the spirit of its time.

Today, of course, we know it simply as the Chukka Boot.

Advertisement for Clarks of England ©︎Wikimedia commons

From the Desert

The story behind the Desert Boot — as the name suggests — begins not on the polo field but in the sands of North Africa. The term came into use somewhat later than chukker, during the early 1940s, amid the campaigns of the Second World War. British officers stationed in Egypt and Libya, serving in what was known as the Western Desert Campaign, found their standard-issue boots far too heavy for the desert terrain.

In Cairo’s bazaars, they discovered a solution: light, sturdy suede boots with soft crepe soles, made in the Veldtschoen construction — a method originating in South Africa. These became the unofficial footwear of the campaign, favoured for their comfort and practicality.

Among those who took notice was Nathan Clark of C. & J. Clark Ltd., himself serving overseas at the time. On his return to England, he developed the design for civilian wear, debuting it at the Chicago Shoe Fair in 1949. When Esquire magazine featured it soon after, the Desert Boot captured international attention — and a legend was born.

In the decades that followed, its appeal only grew. Worn by icons like Steve McQueen and embraced by the British Mods movement of the 1960s, the casual suede boot came to embody a timeless kind of cool — effortless, versatile, and quietly defiant.

©︎The Hollywood Archive | Alamy Stock Photo

Construction and Character

The name Veldtschoen endures today — not as a design term, but as a method of construction. In fact, it is this very method that provides the key distinction between the chukka boot and the desert boot.

In a classic chukka, the upper leather is lasted inside the sole, giving the welt line a tighter, cleaner profile — a look that feels refined and slightly formal. The desert boot, or Veldtschoen construction, takes the opposite approach: the upper leather is turned outward and stitched over a welt attached to the lining, creating a natural barrier against water. As a result, the welt line blends with the upper, and the sole — typically crepe — defines the shoe’s relaxed, utilitarian character.

That said, the distinction has softened over time. After several decades of reinterpretation, many modern boots blur the boundaries entirely. Best, perhaps, to treat it as a small piece of knowledge — something to quietly appreciate, rather than to insist upon.

Click here for the rest of the story (2) ▷.

Text: Shuhei Miyabe | NEGRONI

Cover Photo : 10th July 1964

British motor racing driver Jim Clark (1936-1968) with the manager of Lotus cars, in this photo.

Colin Chapman (1928-1982) in the pits at Brands Hatch in Kent.

©︎ Fox Photos | Getty Images